|

|

|

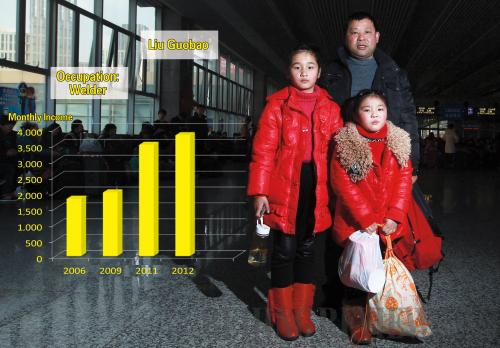

MIGRANT FAMILY: Liu Guobao (behind), a migrant worker in Shanghai, spends most of his income to support his family. The histogram illustrates his average monthly salary between 2006 and 2012 (DING TING) |

Thirty-year-old Ye Lei had worked in a state-owned factory in her hometown Jiangxi Province for seven years. Although she had been promoted to the position of the department head, she quit her job last month to work as a sales representative in a marketing company in Beijing.

"The first thing I want from the job hop is a higher salary. Career opportunities come second," Ye said.

Ye had already received a 13-percent pay raise over the year earlier period before she quit the factory. On April 1, Jiangxi Province increased its minimum wage for the eighth time since 1995. Many workers in Ye's factory have benefited from these wage increases.

Currently, in the most economically developed areas of Jiangxi Province, the minimum wage is 1,230 yuan ($196) per month, or 12.3 yuan ($1.96) per hour. Whereas in some less developed areas in the province, the minimum wage is 900 yuan ($143) per month or 9 yuan ($1.43) per hour.

Even with the raise, Ye still felt her income wasn't keeping up with the increasing cost of living. With profits of the factory dwindling and some of her workers leaving for greener pastures in the service sector, it was time for Ye to jump ship as well.

China's fast-growing service industries are luring workers away from the manufacturing sector. Modest hikes in local minimum wage ordinances do little to staunch the flow of personnel, to which the recruitment postings near the gate of Ye's factory can attest.

A report of The Wall Street Journal presents data showing that in the previous five years, the service industry created 37 million new jobs in China, much more than the 29 million created in manufacturing.

Labor shortage for the manufacture sector in China is not seasonal or short-term, said Kelvin Lau, senior economist of Standard Chartered Bank. Competition for labor is expected to drive up wages.

Stories of wage earners

On May 17, the National Bureau of Statistics of China released last year's average annual wage of the workers in urban non-private sectors, which mainly comprises state- and collectively-owned enterprises and public service institutions. The data show that in 2012, workers in those sectors made an average of 46,769 yuan ($7,459), a nominal 11.9-percent increase over that of the previous year. After deducting inflationary factors, the real annual growth rate was 9 percent.

As often, the release of national salary statistics sparked discussions and prompted people to share their income-related stories.

Lu Mengying, a 31-year-old resident in Beijing, is happy about her current income. She was recently hired as sales representative by a company selling luxury goods.

"My base salary and commission usually add to about 8,000 yuan ($1,276) per month. If things go well, I can make more than 10,000 yuan ($1,595)," she said.

Lu had previously earned rather little at a marketing company in Beijing's Zhongguancun area, China's Silicon Valley, where she had worked for six years after she graduated from university.

Promising earnings prospects drew her to the luxury industry. She enrolled in an expensive training program on luxury industry management. The 15-day training program cost her more than one year's income, but Lu found it worthwhile, as it helped her land her current job.

According to Lu, a "buyer" of a product line under a luxury brand in her company can make at least 500,000-700,000 yuan ($79,700-$111,600) a year. The buyer's duty is to run around the world to collect product information, contact suppliers, place orders and procure products to meet the needs of various consumers.

Currently, buyers are in short supply in China. Lu said that because of her limited ability and her 3-year-old child, she doesn't want to become a buyer, at least not right now. She's more confident about working her way back up to management—of a boutique rather than a factory. Few people in China meet the qualifications for store manager, so such individuals are highly sought after by luxury brands.

Lu's optimism is not unsubstantiated. Last year, a number of international brands exploring markets in second- and third-tier Chinese cities discovered significant demand for sales, human resources, training, business development and leasing professionals, according to a 2013 global salary survey by leading recruitment consulting firm Robert Walters.

|