|

|

|

Ballerina Pai Shu-hsiang (left) in the role of Wu Chiung-hua |

A major attraction among the capital's Spring Festival entertainments is the eagerly awaited reappearance of the new ballet The Red Detachment of Women. The ballet, after its Peking premiere last October, was taken on tour to Canton and Shumchun, and returned to Peking for performances over the New Year. It now incorporates many improvements suggested by the public.

This is the first time in China that a full-length ballet deals with a revolutionary theme, takes the working people as its heroes and heroines, and is understood and warmly liked by audiences of the working people. It marks a first big step towards revolutionizing the ballet in China, and making it national and popular.

The action of the story takes place in the 1930s on Hainan Island off the Kwangtung coast. A young slave girl Wu Chiung-hua, rebelling against the cruelty of the local landlord despot, runs away. She meets a young political instructor of the local Red Army forces, who helps her to join the Detachment of Women. Trained by the Communist Party and tempered in battle, she becomes a staunch revolutionary fighter. After the heroic death of the political instructor, Chiung-hua takes his place and leads the fight. The ballet's scenario is adapted from the film of the same name, one of the most popular releases in 1961. But, comparing it with the film, the author of the original screenplay Liang Hsin says: "It is a re-creation, not an adaptation."

The production is by the Central Modern Opera and Dance-Drama Theatre's Ballet Theatre. Pai Shu-hsiang and Liu Ching-tang, the well-known ballerina and male dancer, danced the leading roles at the premiere.

Need for Modern Themes

Ballet has a history of only some ten years in China, but development has been swift. Many critics have noted the fine technique of Chinese dancers as shown in Swan Lake, Le Corsair, Notre-Dame de Paris (Esmeralda) and other Western classics. But the limitations of the old classical ballet with its princes and princesses, romantic lovers and fairy maidens, have long been felt here. In both content and form, it is far removed from the working people and from modern life. There is also the added problem of giving ballet a national form. Like the other arts it has been called upon to do revolutionary duty, to serve proletarian politics, the workers, peasants and soldiers, and become a powerful instrument in the cause of the class struggle and the struggle to build socialism. Dance-dramas such as The Little Knives Society, using Chinese classical dance and folk dance movements and mime and modern dance on a theme from the Taiping Revolution, or The Five Red Clouds, whose action is laid on Hainan before liberation, had already led the way to modern, revolutionary themes in the dance. With such examples before them, Chinese ballet artists, determined to bring their art into closer consonance with the life of today, decided on staging The Red Detachment of Women as a new ballet early last year.

How It Was Done

The ballet theatre formed a team of three young choreographers, a composer, a decor artist and the main dancers. To get a fuller picture of past revolutionary struggles in Hainan and of the life and customs of its people, they went to Hainan itself. Here they visited Feng Tseng-min, the woman company commander of the former Red Detachment of Women, who told them the full war-lime history of her company. They learnt more from other women on the island, who told of their own lives as slaves in the old society and their participation in the revolution. With such instructors, the picture of the times and the images of the women fighters of the detachment grew more real and vivid in the artists' minds. The scenario, after seven revisions, was finally ready for production.

|

|

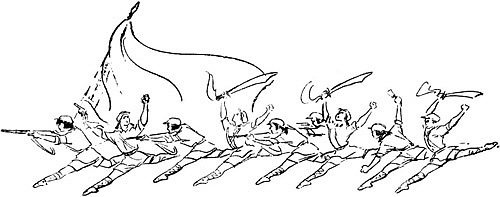

A pair of dancers during the joint celebration of Red Army fighters and villagers (Li Ke-yu) |

The second step was to bring the whole creative collective, including all the dancers, to identify themselves in thought and emotions with the revolutionary fighters whose images they would recreate. This was particularly important for young artists who had scant knowledge of the old society or military affairs. As part of this process, the whole cast twice went to stay with units of the People's Liberation Army, learning from the soldiers and getting training in military exercises. These experiences not only deepened their revolutionary outlook but also provided a more realistic basis on which to create and adapt ballet movements and create new dance movements suited to the new needs of their roles. Following their return, for instance, they choreographed for the corps de ballet a dance portraying young women of the Li national minority on Hainan, but they did it in two versions: one on pointes and the other strictly conforming to an original folk dance of the Li people. After both versions were rehearsed, they discussed the merits of each. The version we see today is a synthesis of the two.

Revolutionary Content

The production, as it is now, has succeeded in adapting the form of the ballet to the content of modern revolutionary struggle. Solos, pas de deux, and dances of the corps de ballet often introduced in the Western classics simply as diverting interludes, have here all been conceived as integral parts of the dramatic development. For instance, in the first scene, the slave girl Chiung-hua has just escaped into the night forest. Exulting in a precarious freedom, she dances a solo that not only expresses her joy but also a certain sense of hesitation as to her next step. The pas de deux when she is caught by the landlord's henchman epitomizes the struggle between the ruthless rulers and the rebellious ruled. Chiung-hua, recovering from her swoon after being beaten and left for dead, becomes aware of the concern of political instructor Hung and his guard who chance to pass by. They tell her how to join the Red Army. At this the trio do a dance which shows Chiung-hua's elation at seeing the way out and the Red Armymen's deep sympathy for a sister from the same exploited class. In the solo of the political instructor before his execution by the enemy, he performs the conventional big leaps and turns of classical ballet but infuses them with a heroic spirit.

|

|

The Detachment of Women (Li Ke-yu) |

The typical danseur noble of the classical ballet is an idealization of the classical hero, the nobleman, somewhat aloof, impassive, magnificent in bearing. Here we have a new danseur heroique who is upright in bearing and morals, vital, intelligent and courageous - a hero of the people.

All these dances have skilfully adapted the techniques of the ballet to the new content and to reflect the sentiments of modern heroes.

Chinese Characteristics

Since the ballet is about Chinese reality, changes in form were clearly needed to project this through the dance. The ballet achieves this, in fact, by skilfully incorporating elements of Chinese classical and folk dance into the ballet style. Chinese classical dance movements are used by Chiung-hua in her solo in the woods; folk dance is the basis of the Li men's Double Knife Dance, the Li women's dance and the joint celebration dance of the Red Army and the people. In the battle scenes, exciting acrobatic movements of Chinese opera, tumbling, somersaults and leaps, have been used to brilliant effect. Such dances of the corps de ballet portraying the Red Army's training as shooting and hand-grenade throwing are modern innovations evolved out of the real-life movements of P.L.A. soldiers.

In these and other ways, the new ballet has made a bold breakthrough in the conventions of the old ballet.

The music, played by a symphony orchestra, incorporates the theme song of the film, but has introduced elements of the music of the local chiungju opera of Kwangtung and folk songs of Hainan. This gives the musical accompaniment a strong national and local colour.

As China's first experiment in this direction, the production is successful. Workers, peasants, fishermen, P.L.A. soldiers, students, office workers and other people who saw it in Peking, Canton and Shum-chun have shown their appreciation by calling for half a dozen or more curtain calls after each performance. Those handclaps meant: Well done! The first step has been taken: it shows great promise. |