|

||||||

|

||||||

| Home Nation World Business Opinion Lifestyle ChinAfrica Multimedia Columnists Documents Special Reports |

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Home Nation World Business Opinion Lifestyle ChinAfrica Multimedia Columnists Documents Special Reports |

| Nation |

| Necessity and Invention |

| Top scientific honor is bestowed upon two of the country's most esteemed scientists |

| By Yuan Yuan | NO. 3 JANUARY 18, 2018 |

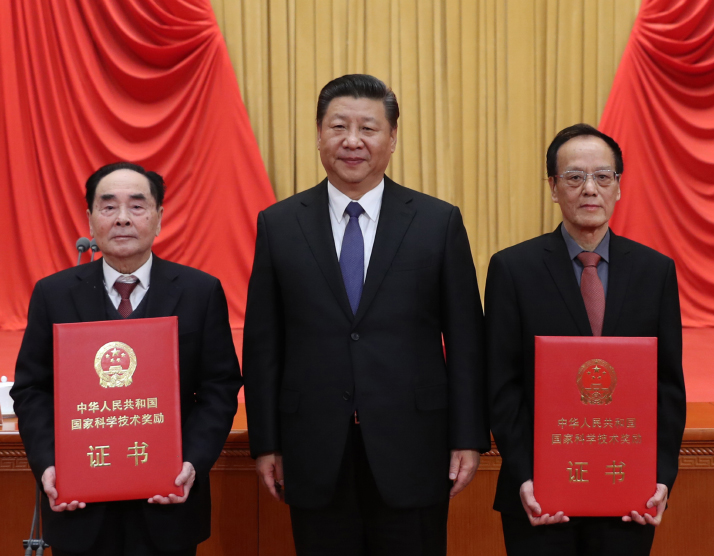

President Xi Jinping presents the top scientific prize to Hou Yunde (left) and Wang Zeshan (right) at the national science and technology award ceremony in Beijing on January 8 (XINHUA)

On January 8, President Xi Jinping presented China's most prestigious scientific prize to two veteran scientists, one a virologist and the other an ordnance specialist known as the "King of Explosives." Sometimes referred to as "China's Nobel Prize," the State Preeminent Science and Technology Award was established in the year 2000. Two scientists are selected annually for the award, and of the 5 million ($768,403) yuan prize money, 10 percent is granted to the winning individuals, while the rest is committed to further research in the field. Notable past recipients are agricultural scientist and "Father of Hybrid Rice" Yuan Longping, who won the inaugural prize, and the Nobel Prize winning pharmaceutical chemist Tu Youyou, who received the award for her discovery of an effective malaria treatment in 2016. This year's winners Wang Zeshan and Hou Yunde were born in 1935 and 1929, respectively, when China was suffering from both domestic unrest and foreign invasion. Throughout their lives, they have witnessed firsthand how the country survived these adverse conditions before going on to make great progress. Their personal contribution to this success is the remarkable work that they have each achieved in their respective fields. Knowledge and power Wang, an academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE) and a professor at Nanjing University of Science and Technology, was born in northeast China's Jilin Province, at a time when his hometown was under the occupation of the Japanese invaders. From 1931 to 1945, the entire northeast of China was occupied by Japan, who established the puppet state Manchukuo in the region. "We were taught at school that we were the people of Manchuria," Wang told China Central Television (CCTV). "But my father told me that 'you are not, you are Chinese.' It was at this point that I realized my country was weak and that we all had to strive in order to make it strong." During this period, Wang resolved to do everything in his power to transform his homeland's fortunes. In his eyes, if China was to be strong, military defense should be a top priority. In 1954, he enrolled at the Harbin Military Institute of Engineering, majoring in the study of explosives. For the time it was an unusual choice, but Wang never for a moment hesitated in his decision. While explosives are fundamental to all military activities, the level of gunpowder production and research of China in the 1950s lagged far behind other countries. Over the next 63 years, ordnance was to be the primary focus of his life and career. "Back then we could only imitate the technology of the Soviet Union, it was a very passive process," Wang said. "We needed to own domestically developed technology, and make it the most advanced in the world." In the 1980s, he made several breakthroughs and solved various technical problems vital to the reutilization of obsolete explosives. In 1993, he was granted to the National Scientific and Technological Progress Award. During the 1990s, he established a new principle of compensation for propellant combustion, resolving the issue of stability in energetic material during long-term storage, and in doing so overcame one of the most difficult technical problems in the history of propellants. In 1996, at the age of 61, he received another national level prize—the National Technology Invention Award. Even retirement couldn't impede Wang's commitment to his research, but rather constituted a new moment in the development of his career. He began to focus on ways to increase the range of China's missiles, committing a further 20 years to this goal. Much of this time was spent in remote and isolated parts of the country, since the nature of this work meant that many of the experiments and tests could only be conducted in far-flung places. By 2016, he and his team had successfully improved the range of Chinese missiles by more than 20 percent. "From simply replicating the technology of other countries to leading the world in innovation, we have proved that China is strong," Wang said. Life guard Virologist Hou Yunde, another winner of this year's top prize, is 6 years older than Wang. While Wang has devoted his life to the development of new technologies for national defense, Hou has spent his fighting battles at a microscopic level through his research on molecular virology and the control and prevention of major infectious diseases. Like Wang, Hou's early life was also filled with adversity. He grew up during the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), and his older brother died of illness when Hou was just 10 years old. It was this loss that made the young Hou determined to become a doctor. In the early 1950s, he enrolled at the Shanghai-based Tongji Medical College, graduating in 1955. He then embarked on a lifelong journey researching countless viruses and diseases. In order to meet international requirements at a time when China was still catching up with the knowledge and technology elsewhere in the world, Hou went to the Soviet Union to study at the Ivanovski Institute of Virology in Moscow in 1958. He returned to China in 1962 with a full medical degree, the first time the institute had granted the qualification to a foreign student. Upon returning to China, he immediately began virology research at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, focusing on various strains of human parainfluenza that were devastating rural parts of the country. Despite various challenges that scientists in China were faced at that time, Hou isolated three strains of parainfluenza in the laboratory, paving the way for a more detailed analysis of the pathogen and the creation of a vaccine in the decades to come. Hou was also instrumental in pioneering China's first genetically engineered drug in 1982. These highly potent medicines can be mass-produced and have saved millions of lives and earned billions of yuan for the national economy since. Following the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic that struck China in 2003, which killed 299 in Hong Kong and 349 in the mainland of China, Hou and his team successfully built a new system for communicable disease prevention, which in 2009 was used to handle the outbreak of H1N1, or swine flu. This system was later commended by the World Health Organization. He also played a major role in developing China's H1N1 vaccination project and in the creation of a disease prevention and control network. The medicines developed by Hou and his team in these years have been used to combat serious illnesses ranging from hepatitis to leukemia. They have saved millions of lives and boosted the value of China's pharmaceutical market from 200 million yuan ($30.7 million) in 1986 to 20 billion yuan ($3 billion) in 2000, according to figures from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Now, at 88 years old, Hou is still working on the frontline of medical research as the chief designer of the national project to combat HIV and hepatitis. Innovation oriented Along with Wang and Hou, seven other scientists and 271 research projects were honored at the annual ceremony. Premier Li Keqiang presided over the ceremony, extending congratulations to the prize winners and calling for more to be done in order to encourage innovation and to protect intellectual property rights. The number of awards at this year's ceremony was 21 percent lower than five years ago. According to Chen Zhimin, Deputy Director of the National Office for Science and Technology Awards, this is a good sign as it sends a message to the scientific community that the assessment procedures are more selective in evaluating the country's discoveries, breakthroughs and contributions. "Evaluation now focuses on quality instead of quantity," Chen told the People's Daily, "and it has become more balanced, more rational and more transparent." In 2017, China made a series of landmark achievements in science and technology. The biannual ranking of the world's fastest 500 supercomputers published on November 13 last year placed China's Sunway Taihu Light in first place for the fourth time. China's fifth research station in Antarctica, which is expected to be set up in 2022, will provide year-round support for scientists. The launch of two BeiDou-3 satellites into space aboard single carrier rocket in November 2017 ensured that China is on track to create a global navigation satellite system by 2020, which will make it just the third country after the United States and Russia to have its own navigation system. China's leaders have placed great emphasis on innovation in the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), with the aim of becoming an innovation nation by 2020, an international leader in innovation by 2030, and a world powerhouse in scientific and technological innovation by 2050. "We welcome all kinds of talented people to participate in China's innovation and entrepreneurship campaign and to share the opportunities and achievements which it will bring," Premier Li said at the ceremony. Copyedited by Laurence Coulton Comments to yuanyuan@bjreview.com |

About Us | Contact Us | Advertise with Us | Subscribe

|

||

| Copyright Beijing Review All rights reserved 京ICP备08005356号 京公网安备110102005860号 |