|

|

|

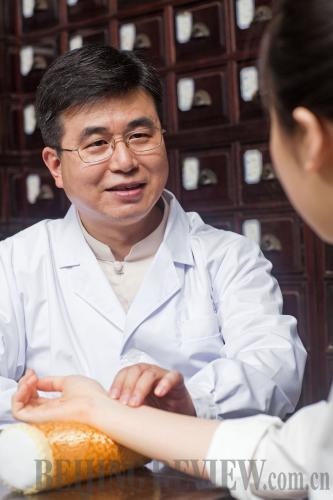

COMPASSIONATE CARE: A doctor of traditional Chinese medicine takes the pulse of a patient (IC) |

When people in the West think about the field of medicine and medical practices, they are often perceived as grim and expensive necessities. Healthcare in the United States, for example, can be frightening for some, as the price tags for pharmaceutical drugs and visits to the doctor are high. Additionally, after obtaining an appointment with a doctor, it can take weeks to be seen. U.S. doctors are harried and overworked, so many are forced to treat their patients in a perfunctory fashion. All of these factors make it difficult to establish an effective working doctor-patient relationship.

In China, however, I have found that this relationship is more kindly, especially among doctors who practice traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Scholars have speculated that the benign quality of Chinese doctors is linked to a cultural norm. It is also thought that because food and medicine are not radically distinct from each other, one might assume that eating Chinese medicine brings people pleasure in the same way that eating Chinese dishes evokes pleasure.

Chinese herbal medicines, like Chinese foods, have certain similarities that may evoke positive feelings. Firstly, like foodstuffs, herbal medicines must traditionally be carefully prepared: They can be boiled, simmered, sautéed and reduced. Picture a loving Chinese grandmother meticulously standing over at a stove at dawn, simmering an herbal concoction for a family member, and then also cooking food for her family. Taking this medicine, like eating her breakfast, conveys much love.

Interestingly, although Chinese herbal blends do not focus on appearance or texture—which are emphasized by culinary laws of Chinese cuisine—preparing both food and traditional medicine are family-oriented activities in China. And, as we all know, Chinese people revere their families.

Several decades ago, Chinese restaurants began marketing their cuisines as healthy. Playing on the idea of serving beautiful, nutritious dishes, some restaurants around China still tout themselves as bolstering vitality, boosting one's immune system or promoting long life. They remind me of the health food café crazes that took the United States by storm in the mid-1980s and again in the last decade, when fitness buffs and eager housewives sat down to raw salads and drinks created from juicing various organic vegetables.

At the same time that the healthy food movement started in China, Chinese doctors of traditional medicine began marketing their medical knowledge and herbal remedies. TCM practices are not focused, as Western medicine is, on specific microbes or specific body areas when curing illness. Rather, TCM addresses the body in terms of systems that are connected holistically, and the concept of a cure is perceived as a process that takes place over time to regenerate health.

Today, among sophisticated, modern urban Chinese families, seeking out a doctor of TCM has lost much of its popularity. Urban families have less time; they don't want to spend hours in consultation with a doctor, discussing their medical history intimately. Nor are grandmothers living in their high-rise apartments willing to rise early in the morning to boil medicine. Such aspiring Chinese nouveau riche prefer to buy tablets and pills, drugs touted on television as providing fast, instant relief for a range of physical ills.

This trend of finding a fast cure, and of buying medicine from those who do not know one's medical history, is part of our post-modern world. Certainly, I have nothing against seeking out a quick cure, especially if the sufferer is pressed for time. But by turning to the fast option, something is missed. Medical science is effective not simply because people have discovered ways to diagnose illness and drugs to overcome it; a psychological component also exists in curing sickness.

The best doctors of TCM emanate a sense of empathy and compassion. These doctors comfort and heal by exhibiting a caring attitude toward their patients. It is the same kind of care that the elderly grandmother emanates, whether she's simmering herbal remedies for her family or creating tasty homemade dishes.

When we ignore the value of this emotional gift, by rushing into a drug store for pre-packaged pills and powders, we are also ignoring the fact that, as humans, we are more than our physical bodies. If a car breaks, one fixes it without emotion. But if a body encounters pain, it needs a holistic cure that treats both the physical and the emotional. When I reflect back on the best meals I have ever eaten, I remember my grandmother cooking for me. Likewise, when ill, I recall the kind face of my TCM doctor.

The author is an American living in Hohhot, north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region |