|

|

|

COURTESY OF CHARLES K. EBINGER |

|

|

COURTESY OF JOHN P. BANKS |

In President Barack Obama's State of the Union address in January 2009, he called for the building of "a new generation of safe, clean nuclear power plants." This was followed by his high-profile speech in Prague in April 2009, in which he noted the need "to harness the power of nuclear energy on behalf of our efforts to combat climate change." In December 2009 in Copenhagen, he pledged the United States will reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions 17 percent from 2005 levels by 2020.

Building on these statements, the administration has made several decisions suggesting a new direction for the long moribund nuclear power industry. To accelerate the expansion of nuclear generation capacity, the president has increased loan guarantees for new nuclear reactors to $54 billion from the $18.5 billion authorized under the Energy Policy Act of 2005. In June 2009, the Department of Energy announced the first four companies eligible for the guarantees, and in February 2010 Southern Company received the first conditional commitment of $8.3 billion to build two 1,100-megawatt units by 2018.

On nuclear spent fuel disposal, the president's proposed 2011 budget cut funding for the long-term waste repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada, after the government had spent 20 years planning and studying the site at an estimated cost of $9 billion. On March 25, 2010, Secretary of Energy Steven Chu appointed a "Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future" to study new policy options for spent fuel.

Are these steps in the right direction to address America's energy challenges? Are they enough, and portend a nuclear "renaissance"? The answers to these questions revolve around addressing four major challenges to significantly expanding nuclear power capacity: cost, safety and security, waste, and proliferation. These issues are rooted in the industry's experience in the 1970s and form the backdrop to what the future holds.

The first commercial reactor became operational in 1957, coinciding with what is referred to as the "Golden Era" of the U.S. electric utility industry—a robust economy, rising electricity demand, declining costs and prices and growth in large generating units. Through the early 1970s, orders for nuclear reactors increased dramatically; by 1970 the U.S. industry had 4.2 gigawatts operating and 72 gigawatts planned.

|

|

|

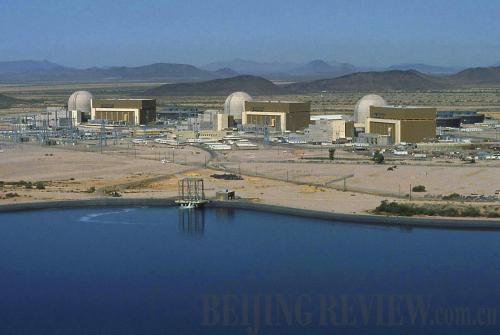

The Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station in Arizona, the United States (XINHUA/AFP) | By the mid to late 1970s, however, several factors converged that would throw the U.S. nuclear industry into reverse. First, a dramatically worsening macroeconomic landscape created financial havoc in the industry. The increase in energy prices as a result of the 1973-1974 oil shock reduced economic activity and savaged energy demand. With stagflation and interest rates at 20 percent, utilities cut back on ordering new capacity, especially large, expensive nuclear units. New nuclear capacity cost an average of $161/kw in the period 1968 to 1971, but costs increased to $1,373/kw from 1979 to 1984. Orders for new units plummeted after 1974 and none were ordered after 1978. In the 1980s, declining gas and coal prices and the introduction of independent power producers further reduced the attractiveness and competitiveness of nuclear power. Operable reactor units peaked in 1990 at 112 and, by 2000, a total of 124 units had been canceled, 48 percent of all ordered units. Eventually the industry was forced to write off nearly $100 billion in stranded assets.

Specific safety events such as the fire at the Brown's Ferry plant in March 1975, and culminating in the accident at Three Mile Island in 1979, also fueled public skepticism of nuclear power and led environmental groups to campaign against the industry across the country. Opposition to nuclear power was spurred further by proliferation concerns emanating from India's explosion of a nuclear device in 1974, using uranium fuel derived from a research reactor.

In September 2007, NRG Energy Inc. submitted the first nuclear license application since 1979, and others followed. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission indicates that as of the end of 2009, it had received 17 license applications (for a total of 26 new nuclear units).

There are several factors driving this renewed interest. First, U.S. electricity demand is expected to increase 27 percent by 2030, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Second, there is growing concern over global climate change, especially energy-related CO2 emissions. With the electricity sector accounting for 40 percent of total U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions and coal-fired power plants representing 50 percent of total capacity, there is increasing concern over how simultaneously to meet electricity needs while reducing CO2 emissions. Since there are no CO2 emissions from nuclear power generation—and it is a proven, baseload source of power, accounting for 20 percent of total U.S. electricity production—nuclear energy is seen as one of the most viable alternatives to address both climate concerns and increasing demand. Moreover, given the recent economic downturn, reinvigorating the nuclear power industry is seen as a way to generate high-paying jobs.

Nonetheless, the lingering historical challenges described above remain and could stall, or at least, reduce the role that nuclear energy plays in the future U.S. energy mix. First, nuclear plants are expensive to build and capital costs in construction are continuing to rise. Recent estimates by Paul Joskow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology conservatively place the overnight capital cost for construction of a new nuclear plant at $4,000 per kw in 2007 dollars (some estimates are higher, including from Moody's in 2007 putting the cost between $5,000-$6,000/kw). This compares with $2,300/kw for a coal plant, and $850/kw for a combined cycle gas turbine plant.

Loan guarantees can provide some help in addressing up front capital costs, but given the high cost of each plant, this approach has its limitations. A better policy would be the establishment of a price on carbon. In Joskow's analysis, carbon prices in the range of $25-50/metric ton of CO2 will be required to make nuclear cost competitive with coal and natural gas, with competitiveness varying with the different fossil price scenarios in addition to any CO2 charge.

|