|

|

|

(LI SHIGONG) |

"No, please don't ask me how old I am; I no longer celebrate my birthday," said one of my expat friends in Beijing the other day. I felt rebuked, almost as if I had insulted her. Certainly, Americans over 30 don't like to fess up to their birth year; their culture denigrates the aging process.

Another friend told me when I asked, "It's hard to grow old in the United States; people ignore you and treat you as if you are either invisible or no longer viable—as if your brain must be slower, your body no longer attractive." In the United States, grandma's and grandpa's opinions are unwanted, despite the wisdom of their years.

Everywhere in the world, China included, I've noted that middle-aged Americans—that means anyone over 50, these days—often focus on doing things that give them the sense of youthfulness. For example, some like going to the gym and doing Bikram yoga, or riding motorcycles wearing sporty clothes.

The illusion of youth is needed to bolster self-esteem. For Americans, old age signifies the end of everything that gives meaning to life: You're no longer sexy; you're no longer wanted at work; you're a potential burden to your friends and family.

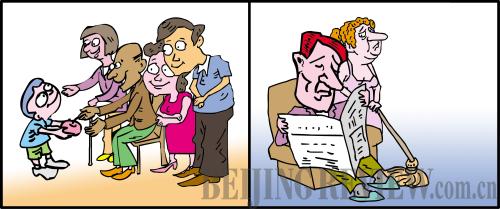

But in China, even today's modern China, age confers honor. My elderly Chinese friends proudly tell me when they were born. They like saying, "I'm 68; I'm 72." Many elders still work, as retirement is not mandatory, especially for academics. Moreover, those who are officially retired are often sought out for their expert opinions. Young people humbly ask them for counsel. Even ordinary seniors receive respect: Youngsters offer their seats on buses to grey beards.

Americans are brought up to be self-reliant. For the young and strong, this presents no problems. But old age can bring a bitter end to independence of all kinds—economic, physical, and social. Living on a pension, with aching bones and no family or friends, is not appealing. Yet many elderly Americans live in this fashion, either by necessity because they have no one, or out of pride, because they loathe the idea of being a burden to their children.

In China the elderly take it as their right to live off the fruits of their children's labors. They live with their children and hold an honored place in the family. Grandchildren adore their elders, who frequently serve as personal caregivers and homeschoolers. Old people have genuine authority and status in the Chinese family.

I can't help but think this way of living is better for everyone, as it serves to enhance emotional bonds across the ages, as well as giving all family members a sense of place.

Once, in the United States a few years ago, I saw my sister's toddler start to cry and point at an elderly gentleman in a cafe. "Why's he upset?" I asked her. "Oh, he's not used to old folks; they look strange to him," she replied nonchalantly. The man sitting near us was hunched over, white haired, and had a cane. He was an object of curiosity and apprehension to my nephew.

Sadly, it's rare to meet an older American who does not refer to his age with either regret or bravado. Many simply refuse to recognize the aging process at all; I've seen American senior citizens in tight spandex and halter tops at the gym. Chinese oldsters are more accepting of their journey through time; they accept physical flaws more realistically—more gracefully. In fact, all the Chinese elders I know bask in their age, as if it were a badge of honor. "By living a long time, they've earned the right to voice their opinions and be listened to with respect," Georgie Wang said. "They feel secure and have a place in the world, an honored place in their families."

In contrast, Americans seek security in individual financial successes. This can lead to lonely lives, disjointed relationships, with old people alienated from their family members. The American Protestant ethic asserts older people must be independent to keep their dignity. Oldsters would rather enter a retirement home than become a burden upon their children. This isolates them even further. Without social interactions among all ages and in different social settings, old people can lose their sense of purpose, and become depressed.

The Chinese have always maintained continuity through the ages. Different age groups have remained mutually dependent upon each other; they have remained emotionally interconnected and respectful of each other. Chinese people do not regard aging as a "battle" or a "problem." Getting old is not a penalty but an honor. What better place do you wish to live, as your bones start to creak, as your hair starts to whiten?

The author is an American who lives in Beijing

|