|

To remain relevant in a time of rapid transformation, government policies, business strategies or the conceptual frameworks of analysts must fully integrate the meaning and effects of the Chinese renaissance, arguably the 21st century's major factor of change.

Just as China needs to create channels to better explain its conditions and intentions, the world has to approach the Chinese continent not as a separate and extinct civilization—sinology as a mere chapter of "Oriental studies"—but as a ubiquitous source of modernity—"global China."

The deepening of a world consciousness depends for a great part on the West's comprehension of "global China" as an actor in history, and on China's capacity to embrace the world with a serene confidence. Trust between the West and China would open an unprecedented era of creativity and prosperity since lasting misunderstandings and suspicions between the two weaken and impoverish the global village.

Unprecedented openness

|

|

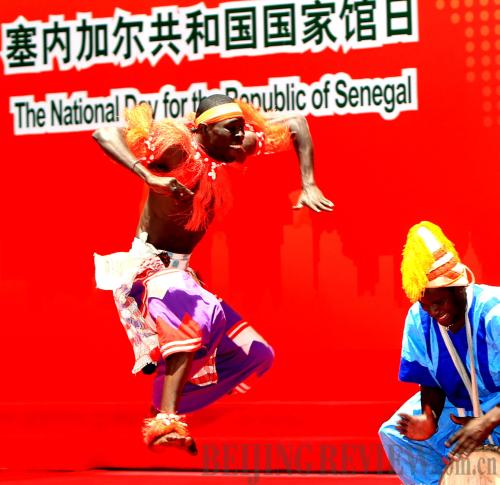

AFRICAN ATTRACTION: Senegalese performers celebrate their National Pavilion Day at the World Expo in Shanghai on July 24 (ZHANG MING) | While the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games have marked China's spectacular re-entry on the world stage, the gradual replacement of the Group of Eight by the Group of 20, induced by the financial crisis, is evidence for the world's elites of China's economic reemergence.

The 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, a comprehensive six-month event involving science, technology and culture, is another important illustration of China's regained centrality and a symbol of globalization with Chinese characteristics.

Within the Expo's site, millions of visitors compare the national or corporate pavilions, discuss their architectural features and the quality of their exhibitions. But it is in the "invisible pavilion" where people coming from all over the world share ideas, impressions and emotions that the most significant exchanges take place.

In the "invisible pavilion," while Chinese visitors have a more direct access to the world's diversity of experiences, many foreigners can unlearn misconceptions about China and make the effort to rethink one of the most consequential dynamics of the 21st century.

The world's most populous country is still often viewed as conservative and immobile, but the perceived empire of rigidity is in reality a dynamic of change whose pace is difficult to capture. In a paralyzed context, China's social and economic problems could not be managed and would certainly worsen, but in an adaptable overall environment these can be solved—and fundamental equilibriums of the Chinese society protected.

Following the Maoist crusade, the "great leap forward" and the radical "cultural revolution," the Chinese people are now adopting the logic of the market economy. Deng Xiaoping's unleashing of reforms in 1978 called for the mind's emancipation and socio-political adjustments that represented the polar opposite of an unprogressive society.

Today's China, far from being immobile, is all about social fluidity, incomparable energy and movement like the "flows of the Yangtze rushing to the East."

China's objective and visible metamorphosis mirrors the flexibility of the Chinese mindset. The transformation of megalopolises or the construction of entire new cities, the development of infrastructure redefining the landscape of an immense territory, the conception of new industrial or hi-tech zones combined with the multiplication of state-of-the-art university campuses, the changes in consumption patterns or even in living habits, would not be possible with a population reluctant to adjust to new circumstances and to accommodate evolving environments.

Michelangelo Antonioni's 1972 documentary China is of great value to appreciate the magnitude of China's metamorphosis—38 years ago Beijing and Shanghai were monochrome, uniform bicycles, the famous Flying Pigeons, omnipresent, foreigners a source of astonishment and fear. In four decades a continent recreated itself.

From a long-term perspective, it is fundamentally this capacity for recreation that explains the continuity of the Chinese civilization. The metaphor of China as a "blank sheet of paper" used by Mao Zedong in his "On the 10 Major Relationships" (1956) is, to a certain extent, a variation on an ancient Taoist principle expressed by Lao Tsu—The great form is without shape.

China's plasticity can appear chaotic but does expand the possible. In the more crystallized West, definitive forms are comfortable but certainly limit the horizon. In Chinese society, behind the official orderly appearance one can always find a more anarchic layer; light easiness compensates the heavy ritualistic decorum, Confucianism and Taoism balance each other.

While many inaccurately perceive China as a static monolith, some also point to an inward-looking, closed and secretive society. Even if one can conceive that intellectual curiosity can largely be satisfied by the internal richness and subtleties of the country, China has, in fact, re-entered a phase of intense communication with the rest of the world. Deng, who as a young man had spent five years in France immediately after World War I, not only put China on the path of reforms but also had the genius to open the country to the world with the strategy of opening up.

As a result, China has never been so cosmopolitan, and even Emperor Li Shimin's Chang'an, the great capital of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), was comparatively less exposed to the influences of the foreign world.

Despite Beijing's ability to modernize and its unprecedented openness, some question China's willingness to act as a responsible global player. However, given the size of its population, China's achievements have global implications. By creating favorable conditions for a fifth of mankind, Beijing is a major contributor to the world's equilibrium. Moreover, the Chinese Government's actions on confronting global terrorism, the risks of nuclear proliferation or the financial and economic crisis, demonstrate that Beijing is a constructive force beyond its borders. A stable and relatively prosperous China is essential to the balance of the international relations. It stands as a promise for developing countries and as a strategic partner for the Western world.

Growing confidence

Does Beijing's overall success, in spite of the global recession, generate self-satisfaction and an "arrogant China?" Is it accurate to present a return to imperial China's sense of superiority, which would be so detrimental for the country's future? One should put the issue into perspective and make a distinction between arrogance and self-confidence.

|