|

|

|

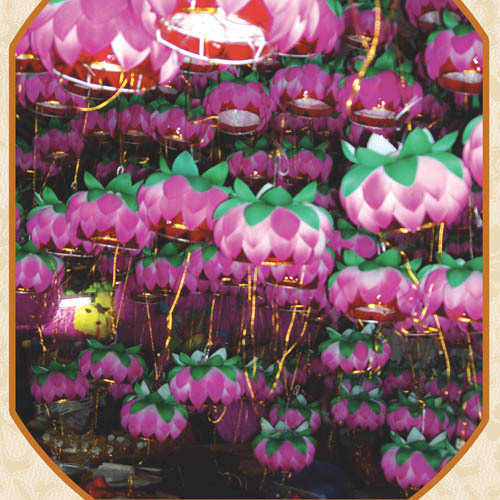

Cao Hong's lantern booth in 2007 (COURTESY OF CAO HONG) |

People in Nanjing City, east China's Jiangsu Province, are quite familiar with lanterns, because of their long history in the area that can be traced back some 2,000 years as well as the annual Lantern Fair on Qinhuai River, a popular folk celebration of the Lantern Festival (the 15th day of the first month in the Chinese lunar calendar) during the Spring Festival.

An old Nanjing saying, "Without visiting lanterns in the Confucius Temple (on the bank of the Qinhuai River), you haven't enjoyed Nian (the Spring Festival); without having a lantern of the Confucius Temple, you haven't had a good Nian," demonstrates the popularity of the fair.

The lantern-making industry in the Qinhuai River area has enjoyed a high reputation since ancient times in terms of vibrant patterns and high quality. The craft of lantern-making has been passed down from generation to generation by family members. The top local lantern-making families include Li, Lu, Cao and Cheng.

A long tradition

Coming from the famous Cao family, Cao Hong, 36, started to learn lantern-making at the age of 5.

"My father told me that he always saw his grandfather making lanterns in his childhood," Cao told Beijing Review.

According to her family records, lantern-making originated from Emperor Kangxi (1661-1722) in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Despite its close association with lanterns, the Cao family did not live on making lanterns.

"My great-grandfather was a farmer who often made lanterns for extra money in his spare time," Cao said. "He made it a habit even though he was busy farming."

Bamboo was abundant at the time. After being split up, the green parts of the bamboo were used to produce crates and kites; the yellow parts were burned for cooking or making lanterns. Kites were produced in spring, while lanterns were made in autumn and sold in winter around the Spring Festival.

Cao Hong's grandfather Cao Zhengzhong was famous for making lanterns and kites before the 1950s; her father Cao Zhenrong, the incumbent Secretary General of the Qinhuai Color Lantern Craftsmanship Association, gives lantern-making presentations around the world.

A forced task

Cao "hated" to make lanterns when she was little.

She helped her father with simple tasks, such as sticking eyebrows on rabbit-shaped lanterns.

"I dreaded vacations at the time, because making lanterns at home was my only 'amusement' during summer vacations," Cao said. "During winter vacations I had to help sell them rather than visit relatives like other classmates did."

In the mid-1970s, she had to work as her father's part-time assistant again, taking charge of making and selling lanterns to finance the family.

Cao chose to leave the industry after getting married in 1997; instead she worked as an operator at a call center. It was an emerging high-paid job that paid almost four times the provincial average. When the industry began to decline, she quit without hesitation and soon found work as a supermarket manager, taking charge of recruitment and marketing.

A new business

In 2008, Cao opened her own lantern workshop after resigning as manager of an office building.

"I actually started making lanterns again in my spare time three years ago, and became a full-time lantern maker last year," she said.

Cao said the hate was gradually replaced by interest. Moreover, she hoped her family's lantern-making skills could be passed on to the next generation rather than vanish with her generation.

"The workshop is small, but I started it all by myself," Cao said. "It's my business."

In order to improve her technique and artistic level, Cao enrolled in courses at the Jinling Fine Arts College in Nanjing.

The courses paid off. The ox-shaped lanterns that Cao specially made for the Year of the Ox this year sold out during the Spring Festival celebration.

Return to starting point

Cao's lanterns are delicate and unique. In addition to employing her family's tradition of making sophisticated and colorful lanterns, she also incorporates new styles and facets into her designs.

Giving up the traditional colored paper, Cao resorted to cloth instead, since cloth lanterns are more convenient to keep than paper ones; the other procedures remain unchanged. But she also produces traditional paper lanterns to cater to different customers.

New ideas sometimes enter Cao's mind while she makes traditional lotus- or rabbit-shaped lanterns. She continually designs new shapes.

According to the Chinese lunar calendar, the year 2010 will be the Year of the Tiger. Cao has already designed tiger-shaped lanterns for the upcoming Spring Festival.

In recent years, mass-produced lanterns can be seen everywhere in the Qinhuai River area, but Cao remains confident in her handmade lanterns, as she believes many people "are still fond of traditional lanterns and are willing to pay more for them."

Moreover, the local government has made efforts to protect lantern craftsmanship in the Qinhuai River area, reserving booths for handicraftsmen in the back of the Confucius Temple for lantern displays and marketing.

"The lantern-making skill merges tradition and innovation," Cao said. By combining those things, Cao has found a way to make a living and keep her family's tradition alive. |