|

|

|

(CFP) |

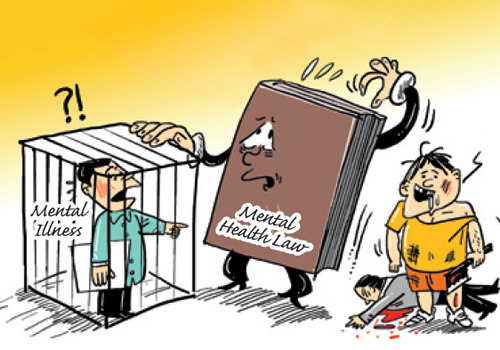

On October 26, 2012, after three readings by the National People's Congress, China's top legislature, the law finally passed. It states that mental health examinations and treatment must be conducted on a voluntary basis, unless a person is considered a danger to himself or others. Only psychiatrists will have the authority to commit people to hospitals for treatment, and treatment may be compulsory only for patients diagnosed with a severe mental illnesses. Significantly, the law gives people who feel they have been unnecessarily admitted into mental health facilities the right to appeal.

The law was first drafted in 1985 and the draft had been repeatedly revised before it was released online on June 10 to seek public feedback.

"It is a big legal step forward to protect the human rights of patients and I hope it can be put into practice soon," blogged Huang Xuetao, a lawyer in Shenzhen, south China's Guangdong Province, after the draft was released. Since 2006, Huang has devoted herself to defending the rights of people victimized through compulsory inpatient treatment for wrongfully diagnosed mental illnesses.

Thirty-year-old Zou Yijun was forcibly committed by her brother and mother to the Baiyun Institute of Psychology in Guangzhou, Guangdong, in October 2006.

Though Zou claimed that she was healthy and was wrongly hospitalized, she was under 24-hour supervision in the mental hospital. Her cellphone was confiscated and she was injected with drugs against her will almost every day. Zou managed to contact Huang who agreed to take her case pro bono.

It was the first time for Huang to deal with such a case. She went to the hospital asking to meet Zou, but was denied. Huang then turned to the media for help and finally, with much legal wrangling and media exposure, Zou was released after three months.

In the background of the legal proceedings, Huang witnessed the deplorable conditions of China's mental healthcare system and subsequently dedicated herself to providing legal aid to people like Zou.

According to the statistics from the Ministry of Health, about 100 million people in China need mental healthcare and among them, 16 million people are suffering from serious mental problems. Mental illness accounts for 20 percent of all diseases in the country and has become a serious threat to public health. The ratio is expected to rise to 25 percent by 2020.

Huang found out that Zou is definitely not the only person to have been treated with unnecessary compulsory therapies for nonexistent mental illness. In 1995, Chen Miaosheng, a former employee of a Beijing unit of Sinopec, China's largest state-owned oil refiner, was sent to a mental hospital by his employer, who said Chen was unstable. Chen remained institutionalized for 13 years until his death at the age of 65 in 2008. Chen's wife sued, but the court found Sinopec not guilty.

What Huang couldn't understand in the beginning was that how come a law on mental health should go so long unratified?

Ma Li, a member of the Mental Health Law research team, said years ago that the lawmaking process had been prolonged not because regulations were difficult to constitute, but because the government couldn't guarantee enough money to enforce them.

"Most general hospitals do not have clinics specializing in mental illnesses and many medical workers, other than psychiatrists and psychologists, lack awareness and fail to effectively identify symptoms of mental disorders," Ma said. "Besides, China only has about 20,000 registered psychiatrists, or 15 psychiatrists for every 1 million sufferers. The number of mental health institutions and doctors lags far behind actual need. All of this needs heavy government investment."

In 2008, Huang, together with other experts in this field, started researching more than 100 cases of forced psychiatric treatment as well as 30 laws and regulations on this subject. In October 2010, they released a report based on the study, revealing the urgency of making changes to the current mental healthcare system.

Based on the research, Huang said that the reason for the law not being formed was not just a simple matter of money. "It estimated that all these problems can be solved with an investment of 3 billion yuan ($480 million)," Huang said. "It is not a heavy burden on the government. There are many other factors to halt the passing of the law."

|