|

|

|

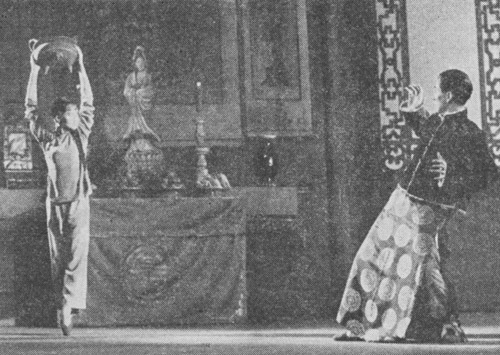

Hsi-erh defies the landlord |

The White-Haired Girl, the Shanghai Dance School's new production, is a new product of the socialist cultural revolution, a good example of proletarian revolutionary innovation. Nightly performances since May Day at Peking's Tianqiao Theatre have been to capacity audiences. Press coverage - editorials, reviews, special articles, sketches and photographs - has been exceptionally extensive and enthusiastic.

Acclaimed as another successful attempt to remould ballet in accordance with Mao Tse-tung's thinking and make it a revolutionary, national, popular art form in China, The White-Haired Girl is a bold advance by a very young troupe. The Shanghai school was set up only in 1960, but it has carried forward the initiative represented by the Peking ballet troupe's The Red Detachment of Women and produced a second full-length ballet that adapts the classical ballet to a modern revolutionary theme. The new ballet is based on the well-known opera of the same name that had its premiere in Yenan in 1944 and, with the liberation, came to be known and loved throughout China, first on the stage and then as a film.

New Emphasis

The story of a poor peasant girl, the original opera tells of the crimes of the landlord class in old China, the terrible oppression suffered by the former poor and lower-middle peasants and their spirit of resistance. The ballet version follows the opera fairly closely but it highlights and emphasizes the law of class struggle that "wherever there is oppression, there is resistance," as well as the truth that only armed struggle led by the Communist Party will bring liberation to the oppressed classes. In its eight scenes and a prologue and epilogue, it brings the spirit of peasant revolution led by the Party to the fore in characterization.

For instance, in the opera, the heroine Hsi-erh's father commits suicide, after he - a poor, debt-ridden peasant - is tricked and forced to sign the deed turning her over to the landlord. In the first scene of the ballet, his hatred for the landlord knows no bounds when he finds he has been tricked and he is killed as he strikes at the landlord and his bullies with his carrying pole. His death and the kidnapping of Hsi-erh enrage the peasants, and, counselled by an underground Party member (a new character introduced in the ballet), Hsi-erh's betrothed and other young men understand that only organized armed revolt can succeed. They go off to join the Eighth Route Army.

Hsi-erh too is a more forceful character than in the opera. Maltreated and a slave in the landlord's house, she is undaunted. When the landlord insults her, she slaps his face and hurls an altar tripod at him before making her escape into the mountains. Fighting the elements and the evils of a corrupt society, Hsi-erh's hair turns white but she is sustained by a burning desire to live and be avenged. When she meets the landlord and his steward in a deserted temple she attacks them and they flee in terror from this "apparition." Meanwhile the people's army has reached the village and called on the peasants to join the revolutionary struggle. Hsi-erh is found. The Party and the army lead her and the rest of the villagers to arrest the landlord and his underling and denounce them for their crimes. The opera ended here with the overthrow of these exploiters and oppressors. The producers of the ballet, wishing to express the thought of carrying on the revolution, have added an epilogue: Hsi-erh is seen marching off with the revolutionary army, a gun on her shoulder, to fight for the cause of the liberation of the oppressed people. The ballet lauds the revolutionary spirit of the poor and lower-middle peasants led by the Chinese Communist Party. It is a clarion call encouraging the people to arm themselves with Mao Tse-tung's thinking, to carry the revolution through to the end.

Ballet Serves Socialism

During the Spring Festival of 1964, the teachers and students of the Shanghai Dance School went to perform for the peasants and units of the People's Liberation Army. They saw the enthusiasm with which the people greeted the new operas on modern revolutionary themes, and asked themselves how they could bring classical ballet to serve the workers and peasants better. The success of The Red Detachment of Women was a big encouragement to them. They were particularly attentive to the passage in Chairman Mao's Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art where he speaks on the question of "for whom our works of literature and art are produced." This, he says, "is fundamental; it is a question of principle." And he points out that revolutionary literature and art should serve the broad masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, should "fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part... operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people and for attacking and destroying the enemy...."

|