| Lifestyle |

| How women's clothes reflect social change | |

|

|

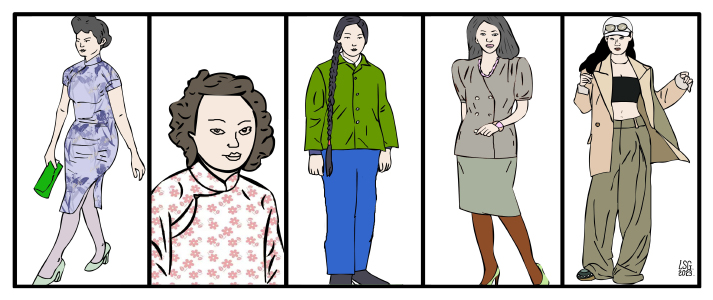

O tempora! O mores! Like it or not, throughout the centuries, almost every civilization has had its own sensitive style issues, especially when it comes to women. Europe had the corset, a tight, structured undergarment extending from below the chest to the hips that was in vogue from ca. 1500 until the early 20th century; China had foot binding. For good measure: One story about the origins of the latter recounts how, during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.)—the earliest dynasty in Chinese history supported by archaeological evidence—a concubine named Daji suffered from clubfoot. She asked the monarch to make foot binding compulsory for all girls attending court so that her own feet would be the standard of beauty and elegance. A token of high-end social status, i.e. not needing those feet to go out and work, for millennia to come, the practice of foot binding gave women the opportunity for upward social mobility. Socially mobile they may have been, yet due to their literal immobility, the women whose feet were bound were bound to their living quarters. Whereas countryside girls with bound feet may have served the economic purpose of creating yarn and fabric by weaving and spinning their hours away inside their rooms, fact remains that with no means to set foot in the real world, women did not play a part in society. Theirs was a man's world. But O, little did they know... How times would change. From restricting practices deemed the epitome of exclusive élan to hip-hop inspired boss swag: One century in fashion reveals the changing role of women in Chinese society. The Roaring Twenties Considered barbaric by modern standards, the practice of foot binding was legally banned after the fall of China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911). But even more important for Chinese women was the arrival of… May Fourth. The May Fourth Movement refers to an intellectual revolution and sociopolitical reform campaign in 1919. It was directed toward national independence, the emancipation of the individual and rebuilding society and culture. The movement created a new arena of liberation for Chinese women. Among other things, they began to look for gender equality in their daily go-abouts, including their dressing habits. A new era indeed required a new wardrobe, one incorporating styles that were considered modern and yet still Chinese, as well as being non-restrictive and allowing mobility. The sartorial freedom arising among young Chinese women reflected the new determination they had to attend college, pursue careers and make their mark on the world. One telltale token of liberation that made its way into the wardrobes of China's female urbanites during this period was the qipao—as we still know it today. For good measure: In standard Chinese, the modern term qipao usually refers to the one-piece female long(er) dress many will know from Wong Kar-wai's 2001 melancholic masterpiece In the Mood for Love. The movie saw the fashion crowd salivating at the sight of protagonist Maggie Cheung's "traditional Chinese" dresses—aka qipao. The In the Mood for Love style came up in the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai around 1927, with the influence of Western culture pouring into the buzzing trade hub. Specially made to accentuate a woman's figure in all the right places and hide or smooth out any "flaws," this newborn dress immediately attracted a large following among Shanghai's celebrities and upper crust. As newly liberated, educated and self-aware women, they expressed themselves in form-fitting, brightly colored qipao that sent one message: Look at me. But O, little did these women know... Tumultuous wartime years were just around the corner, and their ravishing dress designs would soon be gathering dust for decades to come... 'Revolutionary' rage When the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, people were eager to work and rebuild their homes after long years of war. Women also began to pursue their own careers, and opted for suits, overalls and Lenin-style coats. These coats, named after former Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, were double-breasted, light khaki and made of denim. They were simple in pattern but very durable in construction. Lenin-style coats were popular with women in civil positions, while factory workers were more likely to wear dark blue jackets, as reported by China's state broadcaster CGTN in the 2019 documentary Becoming Her: Chinese Women's Fashion Evolution in the Past 70 Years. The decade from 1966 to 1976, also known as the Cultural Revolution, featured a very formal, utilitarian and genderless national "dress code:" the military costume, the work costume and the Mao (Zedong) suit, with little variation in color from gray, green and blue. The fashion was to dress as soldiers, farmers or workers, as these were the most respectable occupations at the time. The uniforms of the professions became everyone's go-to outfit and were the style of the era. In short, over the course of that 10-year period, "liberation" meant that women should become no different from men, wearing men's clothing and behaving in a gender-neutral manner. Needless to say, the overall everyday Chinese aesthetic was looking a little bland. And the country's outlook a little bleak. But O, little did they know... Change was just the flip of a page in the Chinese lookbook away, and soon the women of the Middle Kingdom would get another makeover. A sartorial kaleidoscope When China launched its reform and opening-up policy in 1978, it brought more than economic prosperity. It also brought new options and opportunities to the world of fashion in China. In addition, a kaleidoscope of foreign appearances began to peek through the door once again. Since 1978, Chinese women, especially, have once again embraced the foreign and the modern—first with a sense of curiosity, then by absorbing European and American pop culture. In her 2021 interview with the shishang nainai, this author heard the words "jeans" and "denim" used many times when the women were discussing their fashion experiences as late twenty—and early thirtysomethings living in 1980s Beijing and Shanghai. For good measure: The shishang nainai, literally translating as "fashion(able) grannies," are a quartet of late-aged urban women who have entered the (live)stream of their golden years with gusto, strutting their stuff on catwalks, covers and Chinese social media. They represent the new generation of grandmas who are stylish in the way they live and dress and do not fit the typical cardigan-wearing, permed-hair granny stereotype. "A pair of jeans was always at the top of my must-have list," one of them said. "When someone you knew would travel abroad, in particular to the United States or Europe, you'd ask them to bring you back a pair." And as the country's economic outlook slowly transformed from bleak to blazing, the women of China, urbanites specifically, ditched the dowdiness of the recent past and never looked back. The 1990s was a golden era for Hong Kong movies, TV dramas and music. Big and small screen stars and singers became idols for Chinese mainland youth, who tried to copy their styles. Tousled hairdos, denim jackets and shades became a hit look among "It" girls on and off camera in the 90s. The shishang nainai remained divided on this look, by the way. At the turn of the century, and well into the 2010s, the swift expansion of the Internet opened up a whole new, or should we say a brave nü (literally "female"), world for fashion lovers, with pop stars from the Republic of Korea and Japan gaining foothold—and a massive following—in China. Fashion became all about breaking and bending the rules. Vogue aficionadas and (brave) aficionados alike were mixing and matching patterns and clashing colors and patterns that reflected individualism—to their heart's content. But O, little did they know… This bold experimentation led to what many today consider fashion faux pas—wild hairstyles, blindingly bright makeup and outfits that resembled a spilled paint palette. The Roaring Twenties 2.0 Smartphones and social networks have changed the landscape of fashion, which was previously dominated only by celebrities. And as China's society transforms, its women are overhauling gender lines, incomes, roles and responsibilities—as well as their relationships with (fashion) brands, trends and consumption. Take the year 2020 for example. This was a big one for young Chinese women as there were many heated discussions of female appearance, beauty standards and body anxiety on Chinese social media. Two hit series—TV drama Nothing but Thirty and the reality show Sisters Who Make Waves—debuted that year. Both focused on a similar group: women close to or just over 30, an age when, many in China believe, women enter a new stage of life. Wan Qian, star of Sisters Who Make Waves, became the face of zhongxing, or "cross-gender," style for her signature wardrobe of oversized men's suits. The style lit a torch for a society of millennial and Gen Z women in pursuit of more powerful femininity. Chao-A ("extremely Alpha") and you A you sa ("boss swag") are two more examples of styles that have their roots in China's 2020 "women's movement." Both compliment a woman's independent, "owning it," Alpha-female vibes through their oversized, genderless, laissez-faire flair. The Roaring Twenties 2.0 see womenswear trends in China come and go at the tap of a mobile screen, from robust hiking-inspired outfits to the colorful whimsicality of this summer's dopamine dressing trend, to a proclivity for anything and everything guochao, or "hip heritage" aka packed with elements referring to traditional Chinese culture, and many more. But across the board, one sartorial component continues to stand out as a constant among the ever-fleeting crowd: genderless, oversized streetwear. Two of the most popular features of streetwear in China are its experimental nature and the extremely blurred boundaries of who should wear what. Streetwear is now a fusion of tight and loose, masculine and feminine, luxury and casual. Just like the qipao's tight fit symbolized the liberation of the Chinese woman in the 1920s, the oversized, cross-gender suit of the 2020s puts her right on par with her male peer. Unlike was the case some 60 years ago, her genderless outfit, chosen by her and not for her, comes with some serious panache to boot. This woman is ready for another century of rambunctious, ravishing, fashionable revolution. (Print Edition Title: Scratching the Sartorial Surface) Copyedited by G.P. Wilson Comments to elsbeth@cicgamericas.com |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|